Taranto in late antiquity and early Middle Ages

ITINERARIES AND COLLECTIONS

The reconstruction of the physiognomy of the city in the late ancient and early Middle Ages unfortunately reflects the failure to acquire the numerous archaeological data lost during the works related to the building expansion of the town, carried out mostly between the last two decades of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s In fact, in that period research favored the aesthetic aspect of objects, paying little attention to fragments, structures and earthy stratifications, in particular of the post-classical age; the same problem was felt also in more recent years due to the conduct of interventions of an often emergency nature and the lack of large-scale organic and programmatic investigations.

Taranto in late antiquity and early Middle Ages:

City planning

Public and private constructions

From the mid-4th century A.D. the city’s settlement dynamics started to change taking on a new structure that remained unaltered until the Early Middle Ages.

The finds providing evidence of the urban presence are concentrated in particular in the area of the ancient acropolis and in the eastern district, falling mostly within the previous urban boundaries. The defunctionalization of some sectors is however reflected in the presence of sepulchres such as the funerary hypogeum of Palazzo Delli Ponti in the old city or in the tombs found in the forensic area, symptomatic of the progressive loss of the civil functions of these places following the tax and administrative reform introduced by the Empire.

However, restoration, reorganization and construction of public buildings were still carried out, accompanied by reclamation works and the building of public spaces in the area of Piazza Castello and along the northern slope: by way of example mention can be made of the Pentascinensi thermal baths, of which a commemorative inscription referring to the construction activities has been preserved. Residential buildings, evidence of a rather wealthy urban elite, are located particularly close to the public areas that were still being used.

More substantial changes to the urban layout of the city were made most likely on the occasion of the reconstruction carried out in 967 A.D. by Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros II Phocas. Along the northern shore of the acropolis, the construction area was enlarged by a back-filled area that extended beyond the outcropping rock; work was done in the cathedral area while the eastern side of the acropolis was fortified, as evidenced by the remains found in the Aragonese Castle. Low cost houses were built downstream on long and narrow parcels of land; the upper and lower parts of the city were connected by a road corresponding to the current Via Cava, along which numerous hypogeum rooms have been found.

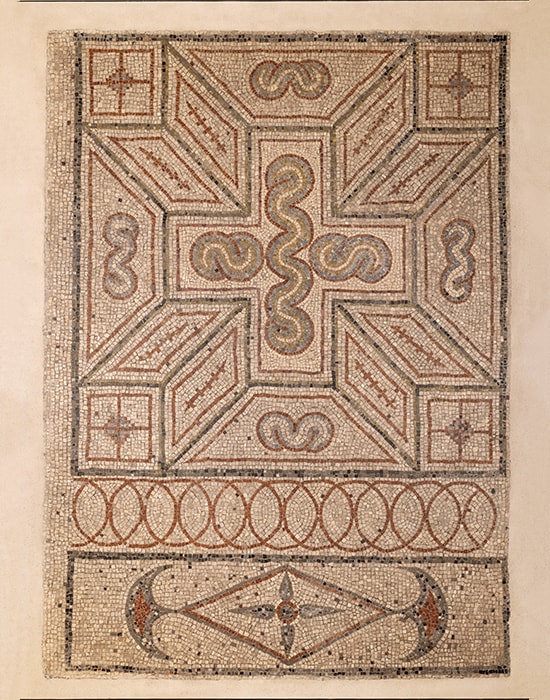

Multi-coloured mosaic flooring, 5th Century AD

Infrastructure

It is likely that the main urban infrastructure in the Late Antiquity and Early Medieval periods was built on the remains from more ancient times. In the area currently occupied by the Romanesque cathedral, for example, occasional excavations carried out in 1931 brought to light the Via Decumana which was still being used, but positioned at a higher level, in the Byzantine period; finally, similar remarks also apply to the defensive walls, which were again rehabilitated on the occasion of the urban restoration of 967 A.D.

The Christian space

There is little certainty as to where the Christian space was located within the urban structure of the city in the Late Antiquity period and Early Middle Ages. The Church of Taranto, like many other churches in the region, is of apostolic origin and can be attributed to the preaching of Saint Peter, a tradition of early medieval origin from which it is not possible to infer any definite historical data. The first literary piece of evidence concerning the construction of churches in the city is the letter sent in 494 A.D. by Pope Gelasius I to the people of Taranto informing them that a new bishop was soon to arrive in the city and that provisions had been made regarding the administration of baptism. Recent studies appear to contradict the interpretation according to which the walls of the crypt of the current Romanesque basilica contain the remains of the Gelasian basilica; archaeological excavations carried out in the area have however highlighted the existence of a place of worship with an apse and a burial ground connected to it, the construction of which may have taken place between the end of the sixth and the beginning of the seventh century A.D. However, there must have been a considerable number of churches in the urban area: diplomatic sources dating back to the year 1080 refer to the presence of seven religious buildings (including both churches and monasteries) besides the cathedral within the city walls (area corresponding roughly to the current historic centre).

The City in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages.

The economy: production, trade and consumption

The economy of the city and of the territory in Late Antiquity still appears to be rather solid, based on the processing of purple dye and on prosperous agricultural activities, as evidenced by the discovery of numerous rural villas. The unearthing of pottery imported from Africa (earthenware pottery, kitchen ceramics, oil lamps, amphorae) and from the East (earthenware pottery, kitchen ceramics, amphorae) demonstrates the emergence of new trade routes to northern Tunisia starting from the 4th – first half of the 5th century A.D. and towards the eastern Mediterranean (in particular towards the area corresponding to present-day Turkey) starting from the mid-5th – 6th century. A.D. The discovery of ceramic fragments from Pantelleria, albeit in small amounts, further confirms the strategic role of the urban port. Finally, there are considerable amounts of local products, which include common pottery for cooking, plain or painted in red or brown in a uniform manner or with geometric motifs that are typical of the tradition of southern Italy, while some are actual imitations of imported products, from oil lamps and furnace waste.

The archaeological data useful for the reconstruction of the urban economy of the early Middle Ages are, on the contrary, more sparse. However, some elements can be inferred from written sources; the anonymous writer of the Chronicon Salernitanum, narrating the Langobard expedition organized in 839 A.D., describes a crowded and rich city, with taverns and markets where food and wines of various qualities abounded and where numerous objects were exhibited for sale, including pottery, and in which the liberators would pose as merchants in order to go unnoticed. The Franciscan monk Bernardo, on the other hand, in his Hierosolymitan Itinerary (approx. 870 A.D.) describes his journey by ship from Taranto to the Holy Land and he reports that in the port he had seen ships loaded with 9,000 Christian slaves from Benevento, thus confirming the trade relations documented also by other hagiographic sources; the same author also mentions the departure of two ships bound for northern Africa and two for Tripoli in Syria.

Tripolitanian lamp, 4th- 6th Century AD

The City in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages:

A crossroads of peoples who were often at war with each other: Byzantines, Langobards, Arabs and Jews

The multicultural nature of the city, archaeologically documented above all by imported objects and funerary steles with inscriptions in Greek, Latin and Hebrew found in the Jewish cemetery of Montedoro, is also described in written sources, where the interactions, however, often appear to be anything but peaceful. As reported by the chronicler Procopius of Caesarea, the urban port was the centre of military operations during the Greek-Gothic war and in 546 A.D. the Byzantine general Giovanni set up his headquarters in the city; again, 663 A.D. marked the arrival in the city of Emperor Constans II who led the Byzantine army and had fought against the Langobards of Benevento. The Byzantines remained in Taranto until it was occupied by the Saracens in 840 A.D. Starting from this moment and for about forty years the Arabs controlled the maritime routes of the Ionian sea, while continuing however to guarantee a certain continuity to the flows of Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. The subsequent Byzantine reconquest in 880 A.D. was characterized by the sale of some of the inhabitants, reduced to slavery; the city was repopulated by people coming from various parts of the Empire, including the Peloponnese.

Stele in Carparo stone with an inscription in Hebrew, 6th - 8th Century AD